Dive

As is true for many, tarot found me in a moment of need. I no longer remember how, exactly, except that astrology and occult practices have been increasingly visible across wider culture, appearing as central plot points in Netflix shows, while such chains as Barnes and Noble stock tarot decks all over the country. What I do remember is the event that propelled me into learning: in the earliest moments of covid-related shutdowns, the university I worked for responded by laying off more than 200 people, including me and nearly all of my friends.

It had taken an immense emotional toll and a lot of work to land that gig in the first place, and my entire identity was wrapped up in university teaching. Knowing how bleak job prospects had been before the entire economy shut down, I very much believed that my career in academia was over. I couldn’t bear, therefore, to think about my work during this period. Previously, I had been trying to pitch my dissertation project as a book, a proposal which had been rejected steadily by a half a dozen university presses over the course of the previous year. How could I think about working on that book when I couldn’t pay my rent? With no job, what was the point?

And yet, my brain needed to be occupied. I was living alone in Cincinnati, while Hannah spent lockdowns in Rome. Occasionally, my friends Yuri and Başak would take distanced walks with me through our local graveyard, a gift to have them close by. But in the unending, undifferentiated hours of those days, before I moved back home and then with my in-laws, what I needed more than anything was something to think through deeply, a rabbit hole I could fall down, unrelated to my own scholarship.

Tarot fit the bill perfectly. It was a system with its own iconography, lore, and hermeneutics. There were different schools of thought, which I could learn about through voluminous literature or podcasts. It wasn’t so much that I needed answers from the tarot as it was that I needed a literature, a language. Eventually, I did read to help understand my own situation, and how I might move forward. But the impulse to research—that came first.

One element of the practice that at first gave me pause was the rather gendered framing that seemed central to interpreting the tarot, and which sometimes resulted in psychoanalytic readings of various mother/father archetypes. I found this alienating to the extent that I find psychoanalysis alienating—not necessarily prohibitive, but you have to do a lot of work to intervene in the gendered assumptions for me to get on board.

What I quickly learned was that there had already been a robust reconfiguration of tarot interpretation that worked explicitly to recontextualize archetypes in a way that wasn’t totally de-gendered, but which de-essentialized gender. The Emperor isn’t a male figure on this view, but a type of energy and orientation that is often represented by/consolidated in men in our culture, an energy that appears in all of us and on which we all may draw. The High Priestess does concern notions of the “divine feminine,” but in a way that isn’t tied to any material or specific bodies. Insofar as both tarot and gender are socially constructed, we have consistently associated qualities of interiority, receptivity, and emotionality with women; what does it mean to think with these energies as they show up in all of our lives, in all of our bodies?

This more expansive and fluid approach to the tarot was spearheaded by feminist and queer readers, who have been designing more and more of their own decks to reflect a less binary understanding of gender identity. As I learned about this turn in the contemporary occult, I also started to notice how many of my queer friends read tarot, or else engaged with astrology, almost a universal. The association between occultism and queerness today seems common-sensical, to be taken for granted. But as recently as 2020, having finally emerged from five years of PhD work, I was beginning a whole new kind of learning.

Surface

My mental state started to change when Sarah Cohen didn’t dismiss my book proposal out of hand. It seemed to me then and still does now that she took a chance on me, maybe not all at once or totally, but enough to have that initial conversation. She gave me a chance to make my work better, talked with me about how to do it, and was ready to keep talking when I had done so. I can’t express my gratitude or how monumental her receptivity has been for my life; it’s no exaggeration for me to say that her willingness to work with me meant I could return, eventually, to the job I love.

Having a book contract gave me something to focus on during the remainder of the covid fallout. Even while unemployed, I could be motivated—my thought was, maybe I’ll never work in academia again, but I can publish my book and say my piece. I’ll have contributed something. This alone got me through.

Eventually, in part on the strength of that book contract, I landed another visiting assistant professorship, not in American Studies (like last time) but in Musicology. My book was published a few weeks before I started teaching at Ithaca College, and I started to dare to have hope again. All the while, I continued reading tarot, learning astrology, and exploring my own identity to the extent that one can in the background of protracted crisis.

Dive

It was not my intention to start writing another book a few months after the first one came out. In fact, I wanted to rest. My course load at Ithaca was 4/4, all brand new preps for me, and some of the classes were upwards of 75 students large.1 The year before, I had been teaching 4/5, a full load at Ohio State plus an adjunct gig in Music History at my alma matter. I was close to burnout, kept going by the pent-up energy of the lockdown period, my desire to go hard while I was able, unsure of how long my opportunities would last. So when, in a casual conversation with Norm Hirschy, he suggested that my idea was too topical to sit on, that he recommended I start writing, that is what I did. Again, I remain grateful to a single editor for having unforeseen and immense impacts on my life.

What I had been talking with him about was my desire to write about a kind of indie rock that had been pulling at my heart for years, a sound that I felt drawn to without really understanding why. I had started trying to figure it out as far back as 2019, when I was preparing a lecture on The Ophelias at Miami. But now I had an opportunity to really dive in.

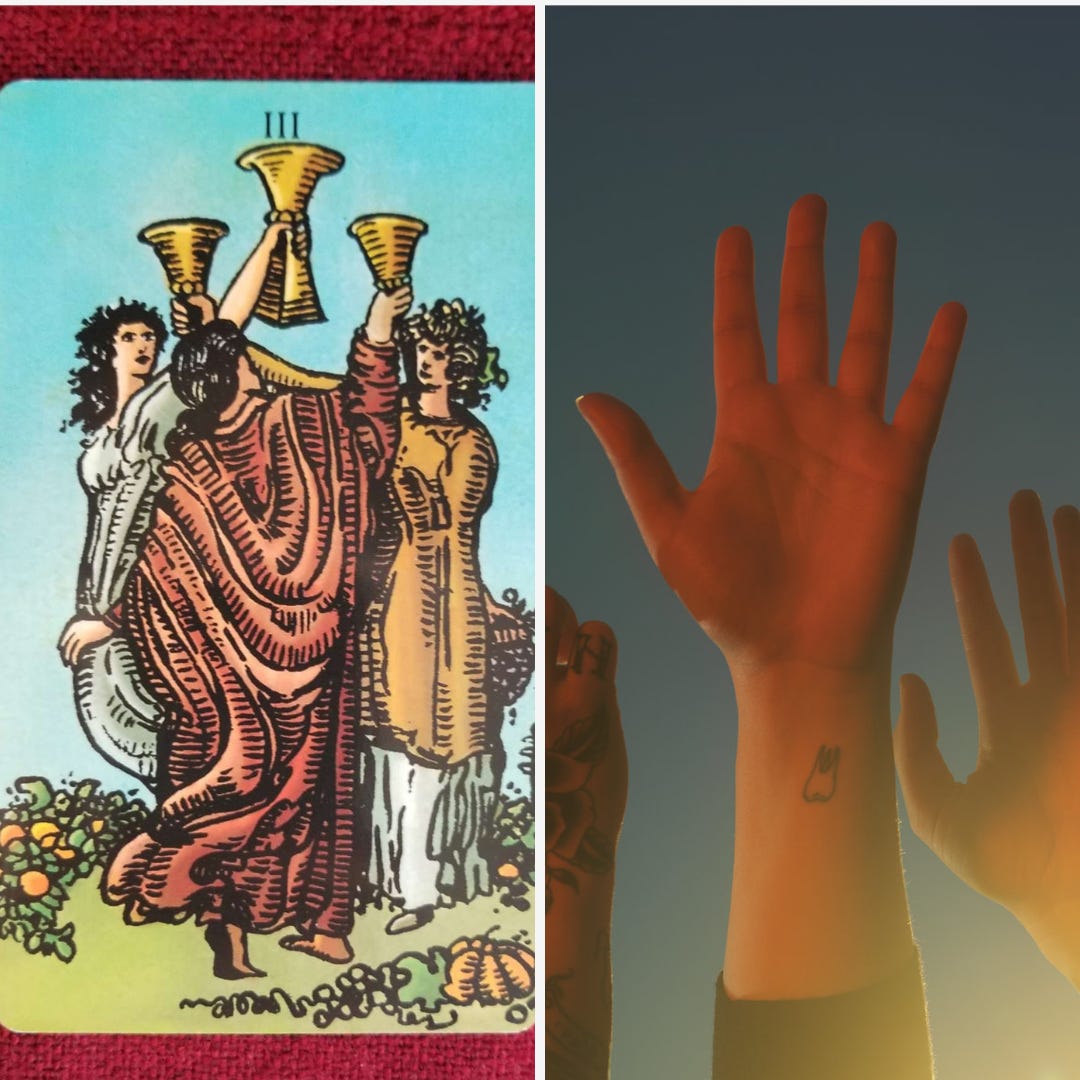

The more I listened, the more I started to hear points of resonance across the bands I was studying: Harmonic vocabulary, certainly, but also more subtle points of reference. Suddenly, my interest in tarot and astrology resurfaced in a more focused way, tuning my attention to song titles like “Scorpio Rising,” “Full Moon in Gemini,” as well as visual references like boygenius’s devotion to the Three of Cups, a counterpart to The Ophelias’s Three of Swords. It became clear that, as much as any lyrical subject matter or common musical approach, occult iconography had become a key means of cohering community around worldviews or sensibilities held in common, what Spencer Peppet calls a “shared language.”

My research had started with the question, “What happened to feminist indie rock after riot grrrl?” In marked contrast to the dominant model of popular feminism performed by pop music’s most prominent figures (Beyoncé, certainly, and arguably Taylor Swift2), indie bands like Snail Mail and Indigo De Souza seemed be taking a different approach to expressing their political views: Namely, they weren’t. While overt expressions of queer desire were becoming increasingly common and increasingly celebrated in the indie space, politics—by which I mean an understanding of the world rooted in the experiences that tend to coagulate around one’s identity position—remained central but implicit, communicated and perceived affectively, by sense.

In other words, rather than articulating a certain political critique in their lyrics, as the riot grrrl movement had done, contemporary queer and feminist indie bands had turned to codes: Sounds, themes, reference points, and visual markers that are meant for in-group recognition only, used to turn heads and consolidate the sensibilities of those already attuned to the frequency necessary in order to understand how, for example, the moon can signal femininity. Suddenly, my accidental interest in the occult meant that I could follow the conversations being shared among this younger generation of musicians in a way that would have been impossible without my own exploration of both queer identity and mysticism alike. Suddenly, and perhaps as intended, I began to feel part of a community.

Surface

These developments have taken place in a broader context witness to increasing adoption of occult practices among marginalized groups in particular, a rise indexed by the kinds of more general pop-cultural phenomena I mentioned in the opening paragraph as much as by signals of academic interest. It is more than coincidental, of course, that feminists and queers often gravitate towards the occult, more than an embrace of something simply because it’s yours. Associated with the monstrous by hegemonic norms, it is no wonder that we identify with the experiences of those perhaps more fantastically aberrant to the normative world.3 What’s more, monsters and witches have powers that normal people don’t understand, powers that are, with the latter category specifically, associated with knowledge practices, research, and non-western ways of knowing.

Associations between witchcraft and feminist politics are so longstanding at this point that it’s difficult to trace an origin; but whatever point we choose, it surely overlaps with the history of the tarot, which, though drawing from much older and more diasporic traditions, first consolidated as such in France and Italy4 in the 15th century (largely through the work of grandmothers). Such associations have been consistently reinforced over time, notably receiving a Marxist/materialist bolster with Silvia Federici’s work in the 1970s, arguably the last moment of “witch craze” in the western popular imaginary.

There have also been critical Black and Indigenous interventions into this imaginary, which both connect to European-derived witchcraft imagery while also showing the deeper, longer roots of medicinal practices, food ways, and ecological knowledges cultivated by Indigenous communities across the planet, regardless of whether or not they are associated with words like “witchcraft” or the occult. In Big Feelings, I write about Kapwani Kiwanga’s work via Kara Keeling (whose first book is called The Witch’s Flight) and Vagabon (a Cameroonian-American artist whose work, I suggest, positions itself in conversation with both women). In all cases, what we may recognize as witchcraft practices help carve out alternative ways of being in a violent world, ways that can help us find a community among whom we can experience a measure of safety.

These variegated but linked practices all conspire to render contemporary mysticism politicized; no mere hobby, all cultural practices are, whether we engage with this reality of not, implicated in politics insofar as politics is understood expansively, as a matter of clashing worldviews rather than narrowly-defined party jockeying; but uniquely and perhaps more than others, to participate in the occult seems to inculcate you into a lineage, something to do with a broader history I’ve only sketched here.

Dive

In the forward to Queering the Tarot, Beth Maiden writes that “seizing the 78 cards we know as tarot and using them to reflect our experiences has become part of our community’s lineage and literary canon” (2019, xiii). This uptake is obviously not universal, either among queer folks or in queer popular music (it is relatively scarce as a reference point, for example, in the kinds of “sapphic pop” I discussed in an earlier post). But in the indie rock bands I’ve been studying, such references are a fundamental part of the vocabulary that can help attune community towards itself, finding strength in recognition.

When I first began thinking about these practices, I had no idea they would find their way into my research. For that matter, I couldn’t have anticipated that my work would would end up sharing something in common with my partner’s: Hannah, a witchcraft (art) historian, has all along helped me to understand the history and accumulation of associations between knowledge, femininity, and witchcraft with queer struggles for liberation—all of which are subjects of persecution in the west, but which, when recognized in one another and across time, help me to feel part of something much bigger than myself.

These days, I am starting to understand more deeply what it means to think about one’s identity as continually in-progress, a matter unsettled. But recognizing the mysticism that had always been swirling around my life, unattended, has helped me to make more cohesive sense out of both my work and my identity, caught up in each other as they always have been. In a period of dizzying instability, this orientation helps me feel more secure than I otherwise would, more prepared to move forward, more capable of finding friends along the way.

(cry hard)

—

Cited

Benshoff, Harry M. 1997. Monsters in the Closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film. Manchester University Press.

Brintnall, Kent L. 2007. “Re‐building Sodom and Gomorrah: the monstrosity of queer desire in the horror film.” Culture and Religion vol. 5, no. 2: 145–160.

Godin, Geneviève. 2022. “Monstrous things: horror, othering, and the Anthroposcene.” Post-Medieval Archaeology vol. 56, no. 2: 116–126.

James, Robin. 2020. “Music and Feminism in the 21st Century.” Music Research Annual vol. 1: 1–25.

Petras, Kim. 2019. Turn Off the Light. BunHead.

Maiden, Beth. 2019. “Forward.” In Queering the Tarot, by Cassandra Snow. Weiser Books.

Stryker, Susan. 2024. When Monsters Speak: A Susan Stryker Reader, edited by McKenzie Wark. Duke University Press.

Vallese, Joe, ed. 2022. It Came From the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror. The Feminist Press at the City University of New York.

For the non-academics who may be here, a course load is how many classes you teach per semester while also fulfilling the research and service expectations in your contract. At “research 1” universities, a 2/2 load (two courses per term) is considered standard for full-time, tenure-eligible employment. Before the days of chronic precarity that have seen around 70% of full-time professors employed in contingent, “gig-economy” style contracts, 4/4—double full time—was pretty unheard of. Now, it’s normal for many, a teaching schedule so busy as to seriously threaten any potential for conducting one’s own research (which is, paradoxically enough, still part of the job you’re often expected to perform).

I think about Swift as more of a postfeminist figure than a popular feminist, but there’s a genuine debate to be had there. Whereas popular feminists advocate a white/neoliberal kind of “girl boss” feminism (more women CEOs of fortune 500 companies! Just as long as they’re pretty and don’t challenge anything about our political attachments to a system of colonial white supremacy!), postfeminism takes for granted that the gains women fought for in the past have already been achieved, holding up one or two token, powerful women as examples that nothing more need be done—especially nothing structural. With my students, I often quip that while both popular and postfeminisms would like to see more women at the board room table, queer, Black, and radical feminisms want the office building raised to the ground. For these feminisms as they relate to and show up in popular music specifically, see James 2020.

For work on the historical associations between queerness and horror genres, see Benshoff 1997; Brintnall 2007; Godin 2022; Petras 2019; Stryker 2024; Vallese 2022, among others.